The extortion phenomenon has changed and many of the entrepreneurs and shopkeepres who accept to pay are complicit with Cosa Nostra.

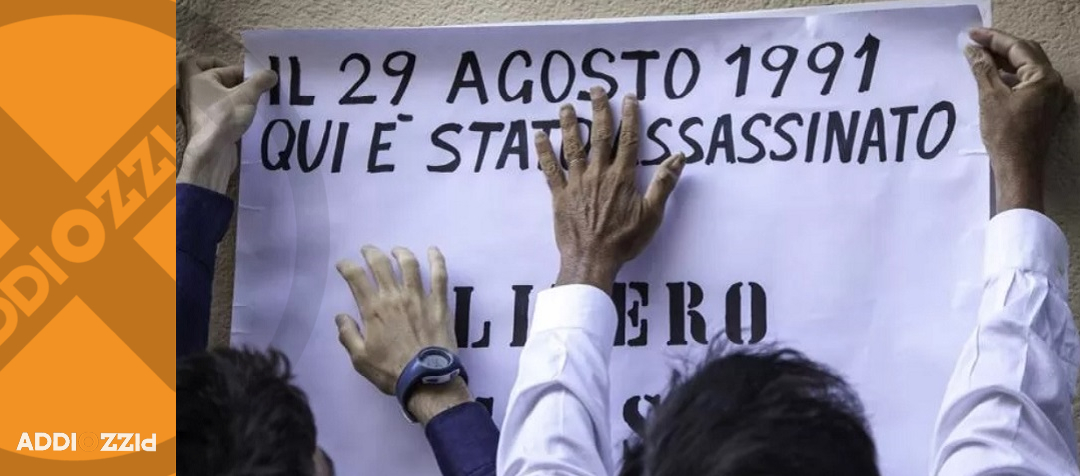

Thirty-one years after the murder of Libero Grassi, thanks to the police and the prosecutors, in Palermo it is possible to report the extortions. The trials of the last two decades show that hundreds of shop owners and entrepreneurs refused to pay Cosa Nostra and had the courage to report. The phenomenon is no longer widespread. Neverthless, there are still people who pay and do not report.

For this reason, it is necessary to redefine our analisys and to update our narrative, taking in count those who pay the extortion and even persist in denying the evidence.

Unlike in the past, today a large number of entrepreneurs pays the pizzo no longer for fear nor isolation, but for connivance. In several trials, relations of serious contiguity emerged between those who pay the pizzo and Cosa Nostra.

There are entrepreneurs who pay the pizzo in order to have services in return. There are those who pay and do not report because they turn to their extortionists to prevent the opening of competitors in their neighborhood or ask them for help with debt collection with their costumers, with settleing disputes with employees and arbitrate neighborhood issues. There are those who pay and do not report because he belongs himself to Cosa Nostra or because the extortionist of the neighborhood is his cousin or son-in-law.

With such cases and relations between those who pay the pizzo and the Mafia, expecting reports or collaborations is an illusion. Hence the need to redefine the analysis. Extortion and extorted people in Palermo no longer have the characteristics of twenty years ago. Many of those who are acquiescent to extortion cannot be considered victims.

In the last two decades, the contrast to the phenomenon of pizzo in Palermo has been marked by a more or less constant trend of reports and collaborations, without exponential decreases or increases.

On the one hand, individual reports, on the other significant even if isolated collective rebellions. . . . . . .

But nowadays, if we want to mark a turning point, we need to start from two essential guidelines. First, the reformulation of the analysis on the phenomenon of extortion, to achieve the adoption of new administrative tools, aimed to make connivance relationships unseemly. They damage the market and sterilize free competition, to the detriment of businesses and consumers.

The second concerns the politics. Those who are candidates to represent citizens cannot ignore the “quality of political consensus“. In April 1991, Libero Grassi argued the need to ban “bad votes collection”.

Shopkeepers and entrepreneurs cannot be asked to report extortion if a good example does not come from our governors and public officers.