Today the sentence of the ‘Alastra‘ trial was has been delivered against people accused of mafia association, extortion, injury and stalking.

Some entrepreneurs were bring a civil action with the support of Addiopizzo.

This sentence marks a milestone on our long and hard route in the territory of the province of Palermo (from Altofone to Corleone, from Monreale to San Giuseppe Jato, from Bagheria to Trabia, Termini Imerese and Cefalù), where we have supported dozens of shopkeepers and entrepreneurswho, after having freed themselves from extortion, continue to work in the area where they have always lived.

While it is evident that the phenomenon of pizzo is no longer as widespread as twenty years ago, we nevertheless need to remark that even today there are those who continue to pay extortion and not report. However, we believe that the media narrative must be reformulated. It is necessary an accurate analysis of the profiles of those who pay extortion and do not report. There are those who pay for fear but, above all, there are those who do it for economic convenience and cultural contiguity.

A strong contiguity relationship between many extorted entrepreneurs and Cosa Nostra has emerged from xeveral investigations and trials. In exchange of the protection money, the ‘victim’ establish a relations of convenience and exchange of favors with organized crime. This happens, for example, in suburban areas of Palermo (such as Brancaccio). In spite of the incessant repression of prosecutors and police and the work of a few social and educational organizations, the territory is characterized by a strong relationship between victims and extortioners, based on cultural and economic contiguity

There are those who pay the protection money and do not report because they turn to their own extortioners to prevent competitors from opening in their own neighborhood. There are those who pay the extortion money and do not report because they belong to the same mafia organization. There are those who pay and do not report because they pay the pizzo to a mafia member, who his cousin or son-in-law. There are those who pay the protection money and do not report because they turn to their own extortioner for debt collection. There are those who pay and do not report because they consult their extrorioners to “settle” disputes with their employees or solve problems with their neighbours.

Considering that, we think that it is misleading to claim that “no one reports the pizzo”, without evaluating the real reasons of it. Starting the specific characteristics of the extortion phenomenon in Brancaccio and in other territories, we believe that the media narrative about mafia, pizzo and their victims should be reconsidered.

The narrative needs to be updated because the extortion phenomenon, its criminal dynamics and the victims tmenselves no longer have the characteristics of twenty years ago.

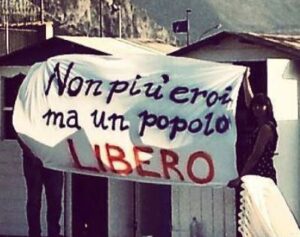

We need to re-write the story as it is different from the one of the recent years, often characterized by the alternation of triumphalist positions and catastrophic ones. The struggle against the pizzo in Palermo during the last twenty years, apart from the significant but limited cases of collective rebellion, points out a pretty constant trend of victim’s collaborations and complaints, without significant decreases or increases.

We need to re-write the story as it is different from the one of the recent years, often characterized by the alternation of triumphalist positions and catastrophic ones. The struggle against the pizzo in Palermo during the last twenty years, apart from the significant but limited cases of collective rebellion, points out a pretty constant trend of victim’s collaborations and complaints, without significant decreases or increases.

In general, the judicial evidence of the last two decades shows that individual, albeit important, stories of rebellion by shopowners and entrepreneurs have been registered in Palermo and continue to be registered. Today they are several hundred and demonstrate that now an anti-pizzo rebellion is possible.